Buildings and Blocks

Space, Time and Lifestyle

Sport-utility vehicles, mobile phones and global positioning systems share in common their military origins. Without a need in the battlefield they'd never have come into being, no less evolved into the ubiquitous conveniences (or encumbrances) that we often take for granted. The effect they've had on the spatial and temporal aspects of our lives is profound. Space is no longer defined only by walls and ceilings, streets and highways, rivers, hills and forests, but by movement through great distances at high speeds. Time has transcended the linear measure of seconds, minutes and hours of the clock, even the natural progression of months, seasons and years. It has been skewed by the frenzy of schedules, the useful life of technological innovation, and the freedom (for some of us) from repetitive labor.

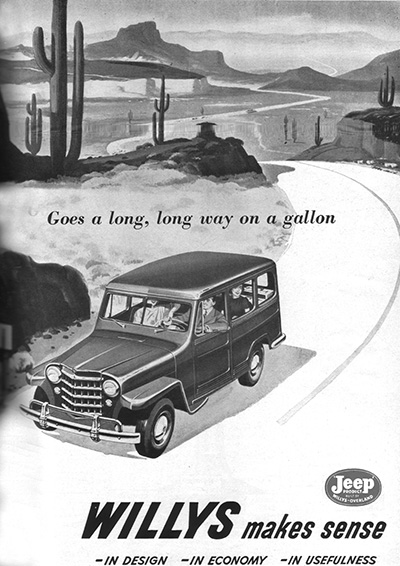

The modern SUV derives from the Willys Overland, a boxy station wagon that appeared in the late-1940s. Based on the military Jeep chassis and equipped with four-wheel drive, the vehicle served the needs and desires of urbanites who escaped on weekends to the country, demanding space, practicality and an "on principle" alternative to the more conventional Ford or Chevy wagons. The Willys was followed by the Wagoneer, then in 1984 by a cleaned-up and trimmed-down version of the Cherokee, probably the first of its genre to combine the robustness of a truck with the handling of a car. The nation had recovered from the oil crisis of the mid-1970s and gas prices had leveled off, but it wasn't until the late 1980s, with the cancellation of the gas-guzzler taxes and a real decline in fuel costs, that the van and utility segment began to significantly expand. Every brand sought its own share of the market: even prestigious Cadillac and Lincoln convinced their traditional customer base to move to bigger, wider, heavier, roomier, and more powerful sets of wheels. Utility vehicles accounted for half of the domestic auto production, forcing the Japanese big three - Honda, Nissan and Toyota - to introduce their own behemoths.

Fueled by the automotive industry's attempt to create a demand for a range of new civilian products following WW II, cruising Main Street (and beyond) became a national pastime in the 1950s. Sprawl generated the need to constantly be on the move, and marked the transformation of lifestyle from urban/pedestrian to suburban/vehicular. The large automobile became a spatial and functional extension of the home: a room on wheels, the telephone and eating booth, delivery van, office, and taxi. Sport and utility, along with comfort and prestige, were joined in one irresistible package.

In this new odyssey, the SUV found its perfect fellow travelers: the mobile phone and the global positioning on-board computer. This tech trio enabled drivers to work from their vehicles, keep in touch with the family, and set out on the road without knowing exactly where they are going.

Justifying the invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003, Vice President Cheney stated that we were not going to have our lifestyle dictated by a bunch of terrorists. Though not detailed, the message was clear: we'd fight to defend our homes, and our homes - functionally and ideologically - included our vehicles and the fuel needed to propel them. Transfer this technology to the battlefield, though, and you have a recipe for disaster. It became evident when US military vehicles began to be blown up by roadside bombs targeting the lifestyle that had become the warstyle - soldiers incessantly, sometimes needlessly, driving around in heavy but vulnerable vehicles, displaying their strength and wealth as if they were cruising down the interstate. Following the timeless premise of The Art of War, if you really wanted to hurt the occupiers, you'd study their excesses and weaknesses, and act on that knowledge. The occupied did just that.

The mobile phone, the descendant of the military walkie-talkie, is the device that is supposed to connect us all in time and space, but the opposite is often the case. I learned about this disconnection in New York when I arranged with a small group of former students to meet for lunch at an uptown pizzeria. I arrived early. Two of the students arrived on time. The other two didn't arrive at all, but after nearly a half hour of waiting, they called their punctual friends at the restaurant to report that they "were on the way." They showed up about an hour late, but, in the new time dimension, what did it matter? Not an unusual story, but multiplied by billions of occurrences, it threatens the performance specification of our society.

The same is true of the global positioning technology, developed by the Department of Defense in 1973 to map the battlefield and determine the precise location of strategic targets. Not only does this system replace the learned ability to read maps, it erodes our innate sense of orientation and direction, primal survival skills that date back to the beginnings of human civilization. The thinking process of finding one's way is reduced to a list of directions or commands: turn left, turn right, continue straight. That may work getting you from your motel to the mall in Paducah (sorry, Kentuckians) or guiding the smart bomb to its target, but it hardly has a chance in Mosul against those who know the lie of the land by heart.

While the rise and decline of empires has historically taken hundreds of years, this one, like others in the past couple of centuries, seems to be happening on an accelerated schedule. So now, for better or worse, we're faced with new constraints and contradictions, causing us to rethink everything from scratch and reassemble the building blocks in fresh, daring ways. It's the challenge of our time.

©2008 Michael Kaplan. This article originally appeared in the Knoxville Voice.

Photo: 1950 Willys Overland, forerunner of today's sport-utility vehicles